This approach based on walking and photographing quickly and freely with the digital camera handheld is quite different to making a photo in a more considered way with a large film camera on a tripod. This approach to photography is based on a pre-visualized object when the conditions were right that is designed to conform to some preconceived idea of what an individual work, or the series, should be.

An example:

Paul Gaffney, the Irish photographer, spells out the differences between these two approaches in this interview with Eugenie Shinkle, a Reader in Photography at the Westminster School of Media Art and Design in London. Gaffney’s excellent 2013 photobook, We Make the Path by Walking, focused on the idea of long distance walking as a form of meditation.

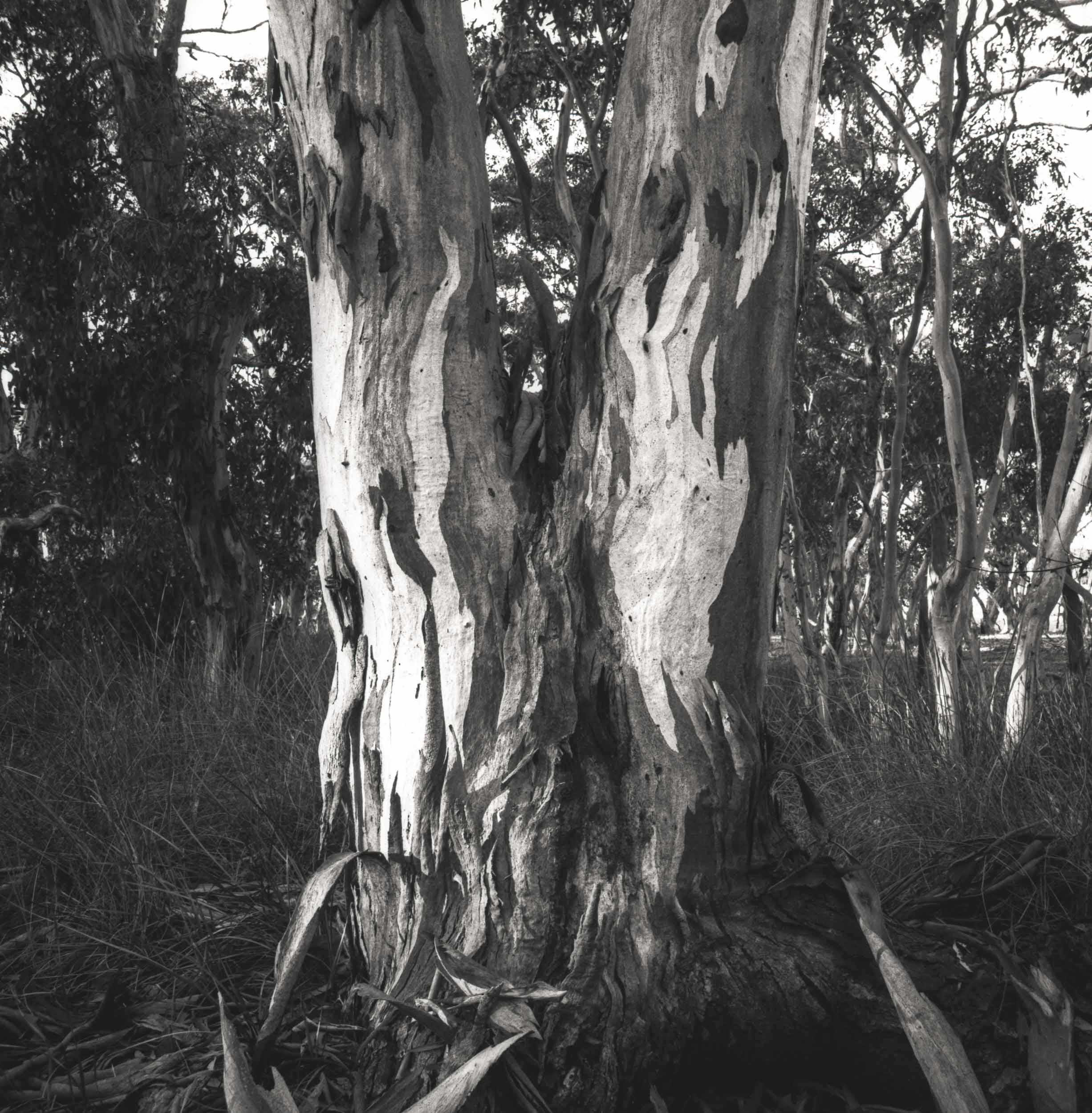

Walking everyday is a key to the meditative mode of walking. When I am walking my interactions are fleeting, and what I am seeing feels more like a bodily reaction to what I saw, rather than a projection of what I was thinking about at the time.

Rebecca Solnit in her book Wanderlust (2001) writes:

“Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord. Walking allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think without being wholly lost in our thoughts.” (p. 15).

Adorno held that every act of “mimesis” must be under stood as“mediated”, which means it cannot be understood as an isolated phenomenon; it is shaped by the “context” of its articulation. The context is the bodily movement of the act of walking also allows us to be bodily immersed in the environment now space, and to see intuitively without being lost in our everyday thoughts. The more I photographed whilst poodle walking everyday in the morning (before sunrise) and evening (dusk) the more the relationship between intuitive seeing, photographing and walking became integrated.

The comportment of memesis is an intuitive way of seeing everything as a whole, or ‘at once’ even though it is a fleeting moment of a multifaceted, complex space that is usually chaotic. Adorno held that memesis is opposed to the desire for self-preservation which leads to the mastery and domination of nature and which generates the drive to abstract conceptuality and knowledge by instrumental reason. Opposed as mimesis is a threat to self-preservation: since it makes possible an awareness of particularity’s refusal to be controlled and fully captured by the concepts of instrumental reason to control nature.

In modernity art presents an avenue in which mimesis can find expression in the sense that memesis migrates into the artwork as the rationality of the artwork that is not driven by the desire for self-preservation and total conceptual abstraction. The latter is where human beings assert their place in the world through the mastery of nature, and by doing so denying their own ties to nature.

In the social order of modernity social order the art work”s concern with sensuous particularity is a privileged domain in which the demands of self-preservation and instrumental reason are relaxed. Art functions as a refuge for mimesis only so long as it is valued by the social order as a non-instrumentalized domain.